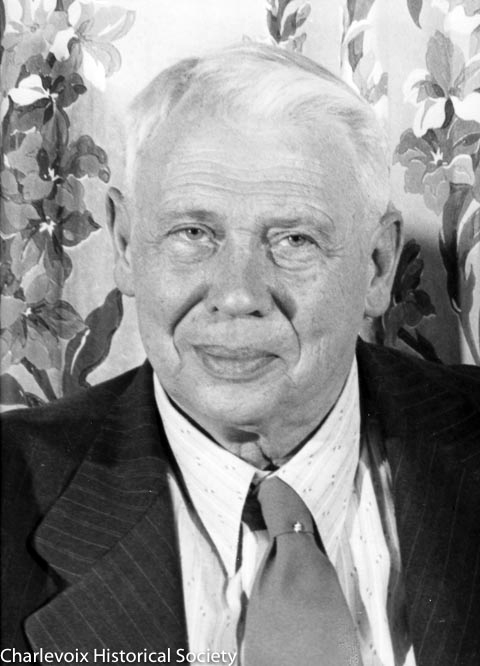

F.F. McMillan, MD: Caring Through the Storms of Life

He arrived in Charlevoix in 1919 to build a medical practice as a new hospital prepared to open its doors.

And despite personal challenges and tragedies, F.F. McMillan, M.D., made his mark as a caring and tireless physician who touched many lives – not the least a grandson who also spent his medical career serving the people of the region.

Dr. McMillan along with pioneer physician and Charlevoix Memorial Hospital’s first administrator Robert Bruce Armstrong, M.D., and a decade later noted physician Gilbert “Gib” Saltonstall, provided a foundation for home-town care that continues today. Dr. McMillan also was instrumental in helping convince the community of the need to build a new hospital on the lakeshore – though he died in 1948 before the current hospital was built.

Charlevoix’s F. James Stewart, M.D., is the son of Dr. McMillan’s oldest daughter, Freda. Though he has but a single faded memory of his grandfather, who died when he was 2 1/2, his grandfather’s legacy was very real as he grew up hearing stories from his mother and his grandfather’s former patients. Because of his grandfather, he also early in life was labeled “Little Doc” well before choosing a medical career. He retired from a Charlevoix family medicine practice in 2015.

Dr. Stewart said when his grandfather arrived from Indian River in 1919, he and Dr. Armstrong carried much of Charlevoix’s medical practice load. “Many of the surgeries were done in homes,” Dr. Stewart said. “I had a patient tell me once that there was a big house on Park Avenue and when she was a child, she and other kids watched my grandfather do an appendectomy through a window.”

The demands on physicians in the early days were great.

Baby Comes During Snowstorm

As a young physician, one of Dr. Stewart’s patients, Julius Elzinga of East Jordan, told him how as a teen he worked in Charlevoix at the livery that was used for night calls by doctors. He slept there and if a physician was needed in the country, he would hitch up a horse, pick up the doctor, and go to the need.

One stormy, snow-blown night a call came that a baby was on the way.

“He was taking my grandfather out toward Norwood and hit a large drift, near where Bells Bay Road is now,” Dr. Stewart said. “The sleigh overturned and my grandfather had his shoulder dislocated. Both he and Julius were dragged under the sleigh.”

Dr. McMillan’s medical bag was flung open and medical tools, bandages and other items were scattered across the drift. Julius received some on-the-job medical training and helped pop the doctor’s shoulder back in place. The physician went on to the farm house to deliver the baby in one-armed fashion. “I used to think to myself when I was called into the hospital at night and driving in a warm car, boy, it’s not like it used to be,” Dr. Stewart said.

In another story about a late night medical mission, that included separate accounts from both his mother and Gilbert Saltonstall, M.D., Dr. Stewart said his grandfather was called out in a severe snowstorm for a birth at a farm near East Jordan. The farmer told his grandfather he would meet him by the main road with a horse and sleigh because the doctor’s car would not be able to navigate the drifts along the country road.

Because the car would frequently get stuck in snow drifts, Dr. McMillan took his daughter, Freda, to help him from behind the wheel when he needed to get behind the vehicle and push it free. The pair arrived at the crossroads with the storm at full intensity. The farmer failed to arrive. As time went on, Dr. McMillan grabbed his bag, made sure his daughter was wrapped in the blanket they carried in the car, and with a small flashlight headed off into the darkness.

“She sat in the car rocking back and forth in the wind until dawn,” Dr. Stewart said. “When he arrived, he just got back in the car and drove them home.” His mother did not know the rest of the story, however Dr. McMillan shared it with Dr. Saltonstall. Years later, he recounted it for his young protégé.

Dr. McMillan, like most physicians of his day, loved his family but was allowed precious little time to spend with them. In 1933, he took his wife and three children to the World’s Fair in Chicago. The theme was “A Century of Progress.” A family airplane excursion above the fair resulted in near tragedy. The plane crashed, severely injuring all onboard.

In Lyla McMillan Arvilla’s account for the hospital’s 80th anniversary publication, she said the plane crashed at Paulwaukee Airport, near Chicago. “It was really windy and the airplane hit a tree,” she said. “Father had a broken shoulder and collar bone. Mom had a broken pelvic bone and multiple injuries. Dad saved her life.”

Her brother, Albert, a senior in high school, stopped breathing and had to be brought back to life, and her sister, Freda, had a broken back and skull fracture. Each member of the family spent significant time in the hospital and was awarded $5,000. Lyla used it to buy the Charlevoix house she lived in for the rest of her life.

Tragedy Strikes Family

Another plane crash a decade later led to heartbreak. Dr. Stewart believes it hastened Dr. McMillan’s death of a heart attack a few years later and also led to his father, Harry, eventually marrying his mother.

When Albert McMillan graduated from the University of Michigan with a master’s degree in forestry in 1939, he was able to obtain a job with the Tennessee Valley Authority in Tennessee. His role involved working with orchard specialists – all in their mid-50s. One of the men became an especially close friend, Harry Stewart.

When World War II broke out, Albert left the TVA, enlisted in the Army and went to flight school. During a training flight near Sumter, S.C., a fellow trainee’s plane flying above him nosed down into his plane.

Albert, his trainer, and both the trainer and student pilot in the other plane crashed and died.

“When my grandfather got the news it really hammered him,” Dr. Stewart said. A photo from 1937 reveals the father-and-son bonds. The pair are standing in Springfield, Ill., looking at a statue of Abraham Lincoln. Their arms around each other as they gaze up at the 16th president.

When Harry Stewart heard about the crash, he traveled to the Army base and collected Albert McMillan’s remains – they were in a shoe box. He put the box in a coffin along with some rocks to weigh the coffin down and locked the coffin. Then he transported it to Charlevoix and the McMillan family.

However, Harry’s show of love toward Albert and the family stirred Freda’s heart. She had a 5-year-old daughter from a previous marriage. However, a relationship blossomed, and they married producing three sons, Jon, James, and Jerry.

In addition to Dr. Stewart, F.F. McMillan’s legacy includes two twin granddaughters who became physicians.

“We are both in psychiatry and my sister has put into practice what our grandfather did,” said Denis Erin Arvilla, M.D., of Charlevoix, who works with her sister Dana Ellen MacMillan, M.D., in Royal Oak. “She sees patients from 4 a.m. to 9 or 10 p.m. and helps people whether they can pay or not. She is an incredible lady.”

During his own career, Dr. Stewart said thoughts about his grandfather always put the demands in perspective.

“It’s humbling. When I was working and tired and would think, ‘Why do I have to work these terrible hours?’ Then I would think about how medicine was practiced in his day and the struggles he must have had to provide good medical care,” Dr. Stewart said. “He would have been excited to see and know the changes in medicine that would have resulted in the betterment of his patients.”

Learn more information about the hospital and the “100 Years of Caring” celebration.