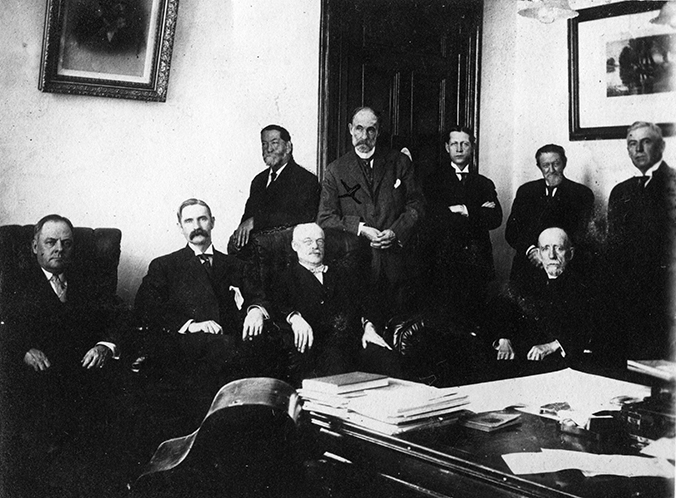

James Decker Munson, MD: ‘A Grand Old Man’

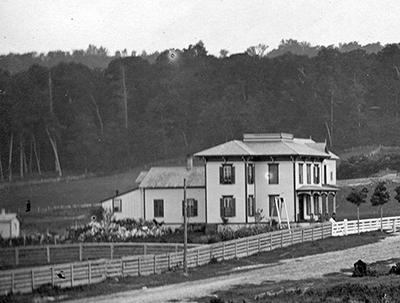

Asylum. (Photo courtesy Traverse Area Historical Society)

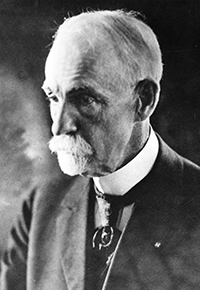

He eliminated straitjackets, advocated for compassionate mental health care, planted trees, investigated Holstein breeding and milk production, and told stories from the downtown barber chair.

And when he did, a lot of people showed up to listen.

Call James Decker Munson, MD, a renaissance man, pioneer, and visionary. He may not have been a Moses, but he certainly turned a lot of untilled, logged-over acreage into a land of promise.

In addition to sought-after medical skills, the 37-year-old Dr. Munson arrived by train to Traverse City in 1885 with 43 patients and a determination that would weather many difficulties and challenges, and instill a culture of care that remains part of Munson Medical Center today.

“Dr. Munson was singularly gracious of manner, winning the confidence of patients entrusted to him, and always possessed of an understanding of their needs,” Edward F. Sladek, MD, told a gathering of medical staff at the Traverse City State Hospital in 1961. “He never lost sight of the beneficial value of the personal relationship.”

Dr. Munson chose the young Dr. Sladek to become his personal physician during the last decade of his life.

His Early Years

Born June 8, 1848, on a dairy farm in Oakland County, just days after the U.S acquired California, Arizona, Texas, and New Mexico for $15 million following the Mexican War, young James would make expanding boundaries a big part of his personal life.

He attended Pontiac schools and high school in 1868 as Civil War veterans flocked to the state to settle the north. He left his farm and agriculture background near Pontiac to attend the University of Michigan’s Medical School. He graduated from the two-year program in 1873, the same year the medical school graduated its first African-American physician – the son of a slave.

After opening a medical practice in Detroit, his skills and reputation began to result in consultations around the region. He served as a demonstrator in anatomy at the Detroit College of Medicine and there, through his first use of a microscope, became fascinated with the microscopic structure of neurological tissue.

He would become an authority on the histological and pathological makeup of neurologic tissue. His interest in general medicine resulted in talks and articles on medical topics.

A New Philosophy

“Dr. Munson caused considerable alarm and criticism when he inaugurated a program of land clearing, draining, and preparation for garden and farm use. The objectors scorned his policy of using inmates for this work,” a Traverse City Record Eagle reporter wrote on July 1, 1924 in an article looking back on Dr. Munson’s life. “Sending insane persons into the forests armed with axes, hatchets, and explosives, they said, was a deadly course. Dr. Munson, however, did not alter his plan. The stumps were blasted and the land cleared and drained by the patients, with no single accident that could be ascribed to their mental condition.”

His alma mater, the University of Michigan regularly called upon Dr. Munson to lecture on mental health. Its 1909-10 calendar of speakers shows he spoke to the Department of Medicine and Surgery on “Insanity.”

His philosophy of care removed the straitjacket from patients, and he instituted a therapy that involved productive work. The farm activities resulted in noted improvement for many of the patients under his care, Dr. Sladek told his gathering in 1961.

“In 1920, it was Dr. Munson’s idea that there was a need for social service case workers in the treatment of mental disease in an institution, and all of you know what that idea has developed into,” he said.

As part of a mandatory report to the state Legislature dated June 30, 1898, Dr. Munson wrote that he had 701 male patients and 618 female patients under his care during the previous two years and that 310 of those patients had been discharged. Of the discharged, he listed 133 as improved, 74 as unimproved, 38 as recovered, and 65 as having died.

“The number of admissions, 306, has not been as great as for former biennial periods, partly due to the uniformly overcrowded condition of the institution asylum, and, as more fully explained in your report, to the beneficial results of State care extending over a period of nearly 20 years,” Dr. Munson wrote. “It is a gratifying fact that the number of occurring cases of insanity within this district have been decreasing for several years past.”

Dr. Munson’s involvement in the local medical society and concern for the community led him to offer the use of a two-story “cottage” at the corner of 11th and Elmwood streets for a community hospital when Traverse City’s only hospital, the Smith Sanitarium, burned to the ground on March 12, 1915. There was no charge for nursing or food. Cost for the patient was $2.50 or $3 per day.

That gift marked the beginning of what would become Munson Medical Center.

The 22-bed facility became a “teaching hospital” where Traverse City State Hospital nurses received general medical training. Funds paid by patients were accumulated until 1921, when the fund totaled $35,000. Dr. Munson understood the 11th Street facility was inadequate for community needs and spent $5,000 of his own funds in 1920 to hire a Detroit architect to draw up plans for a new hospital. Meanwhile, when state officials saw the $35,000 in a general hospital fund on the state hospital’s books, it was moved to the state general fund.

Dr. Sladek recalled Dr. Munson and 30-some other prominent citizens immediately traveled to Lansing to lobby Governor Alexander Groesbeck to return the money as it was intended for a community hospital.

“Governor Groesbeck told this committee, ‘We can’t do anything about this. That money is gone. The only thing we can do is to create in the Traverse City State Hospital a general hospital, and we will put in a bill creating such, we will put in $78,000 to build it.’”

Dr. Munson returned home in victory. The hospital broke ground in 1922 and the Record Eagle gave him credit for making it possible: “The Grand Traverse region owes Dr. Munson a debt of deep gratitude and it is hoped the new general hospital will be a fitting memorial to his untiring efforts on behalf of the people of the region.”

The Final Years

In July 1924, the 76-year-old resigned his state hospital role and retired to his home on Bowers Harbor with his wife. In the words of Dr. Sladek, he was still “a grand old man at least 10 years younger in physical activity and mental activity.”

When the 55-bed James Decker Munson Hospital was dedicated on July 29, 1926, Dr. Munson stepped back into the spotlight. It was the only community hospital in the state under the jurisdiction of a state mental institution.

Marian Ward, a member of a prominent Manistee family, became Dr. Munson’s second wife in 1904. Marian was described in a book of northern Michigan citizens as active in the “leading social affairs of Traverse City” and a “most gracious personality.” She died suddenly from a brain tumor on Aug. 23, 1927.

Historian Karen Rieser wrote in her book, “Notable Women of the Old Mission Peninsula,” that the proprieter of the Sunrise Inn on Bowers Harbor, Mary Kroupa Atherton, lived across the bay from the Munsons. When Dr. Munson needed help caring for his wife, he would run a lantern up his flagpole as a signal for Mary to come over and help.

Ironically, Traverse City’s beloved medical pioneer died after developing pneumonia while trying to recover from a broken leg he suffered getting out of bed at the Pantlind Hotel in Grand Rapids on a trip back from California. He had his chauffer drive him back to his Old Mission Peninsula farm. When Dr. Sladek arrived, the former medical school lecturer refused an X-ray or any extensive care.

“The only thing I could do was practically daily go out there and put on massive elastic bandages to try to give him a little support,” Dr. Sladek recalled. “He lived alone in the house and the caretaker of the farm and his wife would come in and cook the meals and do the housework, but he stayed in the place all alone, which of course is not good for anyone.”

Dr. Munson died on June 24, 1929. He is buried at Oak Hill Cemetery in Pontiac next to his first wife and son.